A tale of two problems - Solving the problem of solving the problem

Often, a solution to a problem is out there - but a working implementation needs to be constructed to meet the needs of the user. Taking that solution and making it useable can be problematic itself. This article details the process involved in solving such a problem on the road to creating a working implementation.

Abstract

Finding the solution to a software problem is often as simple as downloading a package, or cloning a repository. Using someone else’s hard work is a very effective way to solve some of the hardest problems. But what do you do if you can’t find a solution that already exists?

Sometimes, the answer is to create the software. This article talks about that process - researching existing solutions, understanding details found in research papers, creating a working implementation, and finally sharing that solution.

I’m writing this article in the style of a journal entry. The reasons for this will hopefully become clear to you as the article progresses. I will be discussing some of the issues I’ve found while creating both the implementation and the documentation for that implementation.

1. Introduction

Solving a problem can be hard. Using someone else’s solution can be a problem in itself. In this article I’ll discuss a specific problem I’ve recently tried to solve, and the challenges that process brings.

When I first started working full-time on VR applications in Unity back in 2016, many of the tools (both hardware and software) were in a state of flux. Over time, the tools have somewhat stabilised, but there are still moments when a change breaks something fairly fundamental, and needs a proper solution. Unity’s XR Plugin architecture changes brought me one of those breaking changes - namely, losing access to some of the boundary data.

When the boundary data information coming back from the Unity API changed, and I no longer had access to the “Play Area” rectangle, my first instinct was to say “That’s fine - I’ll work out the rectangular area myself. How hard can it be?”

It turns out - pretty hard. Non-trivial, in fact.

As I went through the process of trying to find a simple solution, I also went through the process of researching how other people have solved this problem, and spent a fair few days looking at journal papers describing those solutions. For many of the problems I’ve been trying to solve over the last few years, this is a fairly standard process for me. I try and clarify to myself the problem I’m attempting to solve. I then try and learn what it’s actually called by everyone else in the world (which may or not bear a small resemblance to the words and terms I am already aware of). Then I try and find working code examples (in C# first, as it’s my current favourite language - then in Python, then in any other C-like language, then in any other programming language, then finally in some human language like English, often with mathematical equations).

This has lead me to a startling insight:

The best documentation for a solved software problem is a working implementation with source code.

There are many kinds of documents describing methods to solve mathematical and numerical problems, but a working implementation not only tells you how to solve it - it does solve it.

On the other hand, a badly scanned PDF of a journal paper detailing an abstract solution does not solve the problem. In fact, it often introduces more problems along the way. And that is, of course, if you’re lucky enough to have access to the paper in the first place.

The problem of solving a problem is tractable, but (as far as I’m aware) not discussed as much as I believe it should be.

2. Background

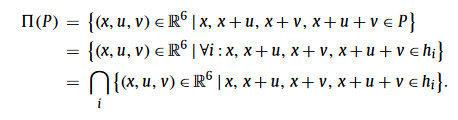

The specific problem I was aiming to solve over the last month (August 2020) was to take a set of points in a 2D plane which describe the boundary of a simple polygon, and from those points, calculate the Largest interior rectangle (LIR) that is contained by that simple polygon. It’s a subset of the Largest Empty Rectangle problem.

The first port of call to solve all of these problems is an internet search. You might find a repository on Github that has a working implementation of a solution to the problem in a language you can use. If there’s not a source option available, you might find a library somewhere that solves it. After that, you’re probably going to need to look at papers, other people’s research, and actually roll up some sleeves and get to work.

Even if you do manage to find relevant research, though - the act of reading, understanding and using that research is, in itself, a non-trivial process.

2.1. Finding the correct research

Most of the papers I’ve tried to read (relating to the LIR problem) such as this one are found as a PDF of a journal paper. Fortunately, in this case it’s a Harvard paper, and there is a direct link available. Many of the papers that it references are not directly available. If you’re lucky, there will be a PDF freely available at a site such as ResearchGate or ScienceDirect.

If you’re unlucky, you’ll run into a referenced paper that you need to pay for. Prices vary, but I’ve seen as high as $40 before. I’m sure that some of these articles are worth the money, but hitting that paywall is a huge roadblock when you’re trying to explore a subject.

This chain of references is necessary to build the accumulation of knowledge required to understand the contents of the paper. If you can’t follow the reference chain, you’re unlikely to be able to accumulate the knowledge. I’ve always thought of this accumulated knowledge as a “base” or “foundation”, but that’s a terrible metaphor for accumulated knowledge. It’s really much closer to a tree, with some form of a shared trunk of knowledge and many twisting branches, often interpenetrating, growing and spreading from that shared trunk.

Some shared basis is always required (for example, algebra, or calculus, or physics - and more specifically, some subset of that domain, for example 3D geometry, or matrix mathematics). Often, this domain knowledge is assumed (rather than explicitly stated). If you don’t have a solid understanding of a domain, then you may need to dive off elsewhere and learn about that domain - which in iself takes time.

For the LIR problem, I needed to refresh my understanding of Eigenvectors, Eigenspaces and Eigenvalues. I vaguely remembered covering these in sixth form, and all that knowledge had subsequently dropped out of my brain. That refresh process involved repeated viewings of Khan Academy videos, other web pages with examples, and coding up test cases in Unity. I found the linked Wikipedia article incredibly dense, and mostly useless as a learning tool.

Finding and exploring the tree of knowledge relevant to your problem space is just the very start.

2.2. Finding the correct terminology

If you don’t manage to find a good starting point on your first (or second, or tenth) attempt, you may need to change the terms you’re searching for. Largest Interior Rectangle? Maximum Empty Rectangle? Biggest Interior Polygon? Contained Bound In Polygon? Some or all of these may get you on to a branch of the research tree. If you don’t luck out on search terms, you might find yourself dangling on a tiny branch, hunting for a solution that’s just out of your grasp.

Once you’re on the tree, you might find that the examples you use make specific assumptions about the terminology that you’re unaware of. For example, all of the related links might happen to use the same names, but not the (slightly different) naming structure used in a different industry. Or the order of operations might be implied to be a certain way round (where everyone else does it the other way around).

Baked into the domain may be a set of assumptions about terms and terminology that make absolutely no sense when examined from the outside. For example, why are loops in computer programs often using the “i” variable? It could be because it’s the first letter of “index”. It could be because mathematical notation often uses i in formulas. It’s certainly never been clearly explained to me, but it is incredibly pervasive. As you begin to uncover the terminology of a problem domain, these assumptions about terms and terminology crop up everywhere, and finding a clear understanding of those most basic parts of a problem description is often in itself a voyage of discovery.

I used the term “sixth form” above - a trivial example of a domain assumption. If you are a reader from a country outside of the UK, you may have no idea what it means, or how it relates to your normal educational age ranges. As a UK reader, you probably saw the words, implicitly understood “the point when he was studying A-Levels”, and carried on with the article.

2.3. Errors and omissions

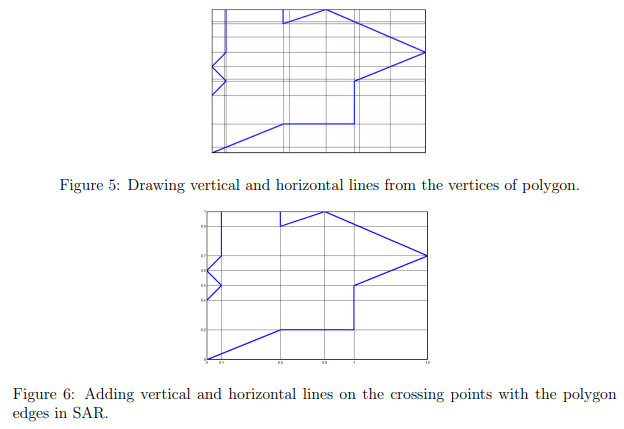

If you do manage to climb the knowledge tree to the point where you understand what you’re trying to achieve, understand the method described in the paper, and feel as though you are ready to progress to an implementation, you’re about to hit yet another human part of the process - errors and omissions. Pretty much every paper I’ve read over the last month contains typical human errors. Spelling mistakes. Mis-labelled images. Out-of-order steps and figures. Examples using one way of doing things (for example “Left then Right”) in one paragraph, then followed by another way (“Right then Left”) in the next paragraph.

Human error is both understandable and inevitable. One way to mitigate errors is to have someone else look over your work (which is an assumed part of the academic journal process). It’s unlikely that you will catch all errors. A better way is to be able to share a document (or an implementation) and allow others the ability to change it directly (for example, a pull request on a repository, or a wikipedia edit).

Similarly, domain knowledge may simply be elided or ignored entirely. “Left as an exercise for the reader” crops up occasionally, which may be helpful in a text book, but certainly doesn’t make constructing an implementation any easier. “This is simple and needs no more explanation” also crops up occasionally, which may be the case for the authors, but is rarely the case for a reader. (If it were that simple, a comment to that effect would be unnecessary).

2.4. Scans, Cut-and-paste, Mathematical equations and symbols

On the off chance you’ve found the perfect paper, you decide to follow the chain of references, and you click on the link. Nothing happens - because it’s not a link. It’s a line of text, in a non-hypertext document. If the paper was written in 1970, this can be excused. If it was written post 1990, then it really should be a document leveraging the best display and linkage options available.

Many of the papers I’ve read over the last month are in a format such that you cannot cut and paste from the document. Many of the papers don’t have hyperlinks for their references. Often, the papers contain mathematical equations, and if those equations contain certain (domain-typical) symbols, finding what that symbol actually means is, itself, a voyage of discovery. Even if you can understand the symbols, understanding the equations themselves may require specific domain knowledge which can take time and effort to acquire.

I’m not arguing that a mathematical equation is a bad way to represent mathematics. I do believe, though, that examples can be shown in the specific, which (for me at least) give some kind of context to the equation, and possibly more insight into the meaning of operator symbols or naming symbols.

3. How to make your research more accessible

As a person creating some documented research, you are undoubtedly under a variety of pressures - usually with the need to justify the research money way up at the top, possibly in tandem with the need to fight for a grant, or a job role, or many other things not directly connected to the actual research itself. These pressures are expected, and I have no silver bullet to help you relieve them. If you want your research to really have an impact, though, here’s some steps you can endeavour to take which will help make your research useable by future generations. If you can do any of these things, you’re helping.

- Make your research freely available.

- Where you can, make it searchable and selectable (including equations).

- Provide specific examples alongside general formulae.

- Provide a code repository with a working implementation.

- Provide links to other resources where possible (not just references).

- Make your research a living document (and open it to collaborators).

What’s the payback, you ask? Immortality. Betterment of the human condition. And possibly, fame and fortune. What’s not to like?

4. Conclusion

If you’re making a paper detailing a solution to a problem, the two core factors are these:

You are advancing human understanding by solving a problem

and,

You wish to share that solution with others.

There may be a hundred other competing priorities, but you should try not to let them stand in the way of the best possible version of your work that satisfies these core factors. Once you have made your work as available and user-friendly as possible, people will be able to carry that work forward and use it solving problems you might never have expected.

I finally struggled through the knowledge tree to the point of being able to construct a working implementation, and in the spirit of this whole post, I’ve also made as much effort as I reasonably can to make it useful and useable by any interested party.

If you’re interested in the implementation details for my solution, please take a look here.